Could UK be forced into quick EU exit?

- Published

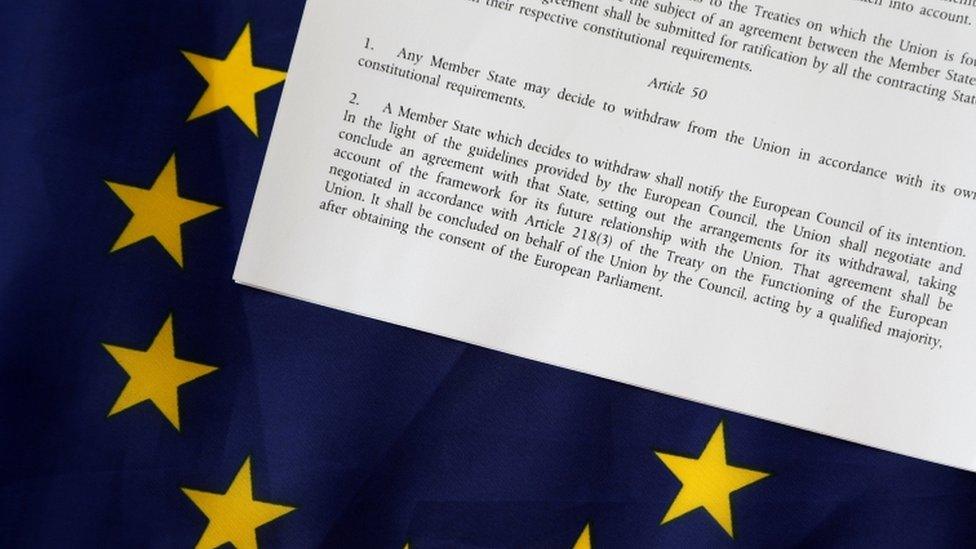

Lawyers are studying Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty

We have voted to leave the EU but when will we actually start negotiating our exit?

There is lots to discuss with our EU colleagues: what to do with half-used EU budgets and EU citizens living in the UK and British citizens living in the EU. There is also, of course, the thorny issue of Britain's future trading relationship with the EU once we leave.

So you might imagine everyone will want to crack on as quickly as possible.

And certainly that is the view of many EU leaders. They want to end the uncertainty for the markets and begin formal talks.

The only problem is that David Cameron wants to delay the start of exit talks until a new Conservative leader has been elected in October.

That would give the new prime minister the chance to work out his or her negotiating strategy and get it endorsed by the House of Commons in a vote - and perhaps even the people in a general election.

But Derrick Wyatt QC, emeritus professor of law at Oxford University, told me that Mr Cameron might not have as much time as he had expected.

Withdrawal agreement

He said that the European Council - representing the 27 other member states - could trigger the negotiating process as soon as the prime minister discusses Brexit with other EU leaders.

Paragraph two of Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty says that "a Member State which decides to withdraw shall notify the European Council of its intention".

Once this happens, the leaving state has up to two years to negotiate a withdrawal agreement.

The treaty does not say how this process of notification should happen.

It has always been assumed that this would come in the form of a letter from the prime minister to Donald Tusk, the European Council president, and the timing would be in the hands of the British government.

Prof Wyatt, who has represented clients in hundreds of cases before the European courts, said that EU lawyers might consider any discussion about Brexit between Mr Cameron and Mr Tusk and other EU leaders as effectively notifying the European Council of the UK's intention to leave.

Weaker position

Prof Wyatt said: "If David Cameron attends the European council on Tuesday, he is likely to confirm in discussions with other heads of government that the UK intends to leave the EU.

"He might do this directly in so many words or he might conduct conversations predicated on the UK's departure from the EU, such as suggestions that informal pre-negotiations might take place before Article 50 is formally triggered.

"EU lawyers might advise the council that such confirmation or such conversations are themselves enough to trigger Article 50 and set the clock ticking on the two year period for negotiating a withdrawal agreement."

But a European Council spokesman reiterated on Saturday that triggering Article 50 was a formal act which must be "done by the British government to the European Council".

"It has to be done in an unequivocal manner with the explicit intent to trigger Article 50," the spokesman said.

"It could either be a letter to the president of the European Council or an official statement at a meeting of the European Council duly noted in the official records of the meeting."

This question is crucial because the sooner Article 50 is triggered, the less time the UK will have to secure a withdrawal deal.

The closer the UK gets to the two-year deadline, the weaker its negotiating position.

Hostile act

The two-year period can be extended but only with the agreement of all EU member states and they would demand concessions from the UK before giving that agreement.

Leave campaigners have long argued that the government should delay triggering Article 50 until substantial pre-negotiation talks have taken place between the UK and the EU. But Prof Wyatt's interpretation of the EU treaty suggests this would be difficult.

Any decision by the EU to trigger the Article 50 process before the UK is ready would be considered a hostile act by the British government and would be a high-risk strategy for EU leaders.

The UK might try to challenge the decision in the European Court of Justice, which decides how EU treaties should be interpreted.

The irony of a pro-Leave Conservative government having to appeal to the very European judges whose legitimacy it questions would not be lost on Remain campaigners.