Patient safety - will there be a big step forward?

- Published

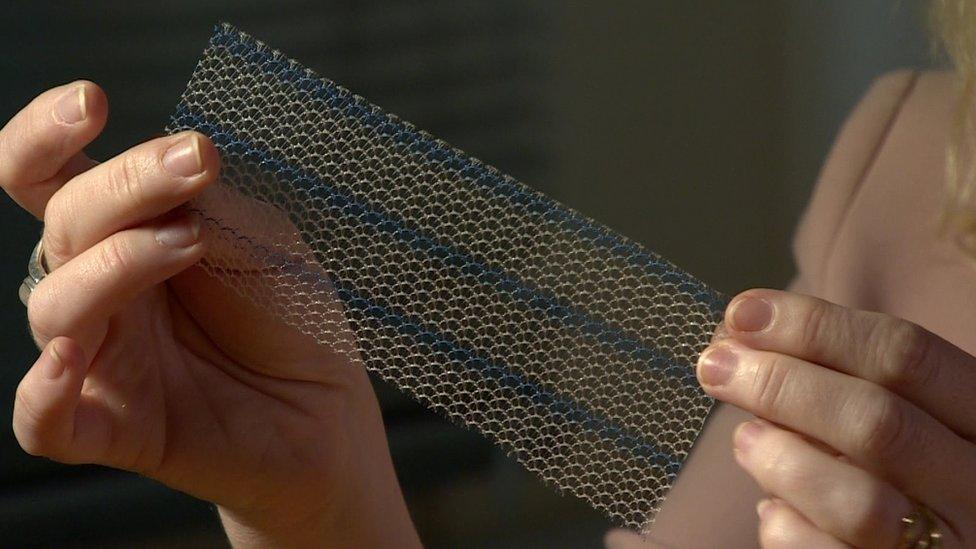

Mesh implants - the latest patient safety scandal

The list is a dismal and shameful one - Mid-Staffordshire, Morecambe Bay, the rogue surgeon Ian Paterson, maternity care at the Shrewsbury and Telford.

All are patient safety scandals involving tragic stories of life-changing mistreatment of patients and, in some cases, the loss of loved ones.

Pledges have been made that patient safety will be put front and centre of health policy. New regulators have been put in place. But now yet another review has found the health system in England to be "disjointed, siloised and defensive" and that the culture needs a shake-up.

It has called for a new patient safety champion with legal powers to be put in place.

The Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review, chaired by Baroness Julia Cumberlege, a former health minister, pulls no punches.

Its inquiry into the suffering and complaints of women treated with vaginal mesh, the hormone pregnancy test Primodos and the epilepsy drug Sodium Valproate found that the health system didn't know the scale of problem, even though tens of thousands of patients might have been affected.

There was a "notable failure" to take action when things had obviously gone wrong.

So what will a Patient Safety Commissioner mean?

The plan is to have an individual with "real standing" outside and independent of the system, accountable to the parliamentary Health and Social Care Select Committee.

The Commissioner would be expected to take up and investigate patient complaints where appropriate, and hold organisations to account - the review had stated that the failure of health authorities to respond to concerns was a recurrent theme.

A model is the Childrens' Commissioner role, the post held currently by Anne Longfield.

One of the review panel members, Sir Cyril Chantler, argued that if such a Commissioner post had existed before there would have been no need for this latest inquiry, as the Primodos, Valproate and mesh scandals would have been dealt with.

Above all, the panel said, there had to be a change of culture, and the establishment of a Patient Commissioner should act as a wake-up call. Although the review remit covered England, the team took evidence from women affected in all parts of the UK.

The review team argues that the new role is needed even with an existing Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB) and Parliamentary Health Service Ombudsman system.

Baroness Cumberlege and her colleagues say bluntly that these two bodies were in existence through at least some of the years covering the three scandals, but did not come up with solutions.

They claim that the remits of HSIB and the Ombudsman are too narrow, and that only a limited number of complaints are followed up.

It is a scathing indictment that, even after previous instances of patient mistreatment, and repeated calls for lines to be drawn and new safety regimes established, another review has found systemic faults.

Kate Langley, Marie Lyon and June Wray have all been affected

Jeremy Hunt, the former health secretary who commissioned the Cumberlege review in 2018, and a long-time advocate of an improved safety culture, said that there were still "many quangos in healthcare, but none which can truly claim to give individual patients a voice when things go wrong".

In all of this it is important to note that the NHS across the UK is respected globally as a safe, efficient and caring healthcare provider.

The coronavirus crisis has highlighted the quality and dedication of health staff. Millions of patients in the UK are grateful for top-class NHS care, but that does not mean failings can be downplayed and lessons not learned.

Ministers will now go over the review recommendations.

The Health Secretary Matt Hancock has already made an apology on behalf of his department to the women affected by the scandals.

Questions have been asked at Westminster about whether another "tsar", this time to run patient safety, will serve a useful purpose and not just add another layer to an already complex regulatory system.

Mr Hancock will have to weigh up whether culture change can be driven by existing leadership or whether a new high-level statutory official is required.

The Cumberlege review has left him in no doubt that it believes nothing short of a new legally empowered patient champion will be acceptable.