The mystery behind Northern Ireland鈥檚 拢26.5m bank heist

Glenn Patterson, presenter of The Northern Bank Job

It begins with a knock at the door. A Belfast suburb, a Sunday night in December 2004. A young man named Chris Ward gets up to answer. A man stands there.

"I’m here to talk to you about Celtic," he says, and Chris, who is Secretary of a Glasgow Celtic Supporters’ Club tells him to come inside. At which point, the man tells him this isn’t about Celtic at all. It’s about his job, at the Northern Bank in Belfast…

Wait. Wind back ten years: 1994

At the end of August that year, the IRA declares a ceasefire after a campaign lasting 25 years. I phone my Mum. "Do you think that’s really it?" she asks. "I think it might be." A couple of months later, Loyalist paramilitaries follow suit. Then in 1998 comes the Good Friday Agreement, with the promise of nationalists and unionists sharing power. I remember the unseasonal Easter snow, and the sense of euphoria.

Over the next few years, the police service is reformed, paramilitary prisoners are released; many of the bellicose murals, for which Belfast in particular is known, are softened. Gardens of Remembrance appear, usually created by paramilitary organisations themselves.

-

![]()

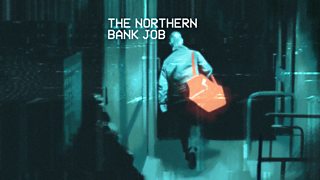

The Northern Bank Job

Days before Christmas 2004, gangs of armed men took over the homes of two Northern Bank officials in Belfast and County Down. The hostage-taking was part of the biggest bank robbery in British and Irish history, sending shock-waves through an already faltering Northern Ireland peace process. Download and listen to the podcast now.

Almost from the start, though, there are things going on… I nearly wrote "around the edges", but that would be to marginalise the victims: so-called "punishment beatings", usually inflicted on young working-class males, murders of alleged drug dealers. And there are robberies too: a million here, two million there – on one occasion five million – all displaying a high degree of organisation, almost military planning. Or paramilitary.

An audacious robbery

The year up to December 2004 has been typical – intensive talks between governments and the parties here about restoring the Northern Ireland Executive… and a spate of "tiger kidnap" robberies, blamed on the IRA.

Still, it is nearly Christmas: we have just had our first Christmas Market in the grounds of the City Hall.

The robbery may have been big, it may have been in one sense clever, but it certainly wasn鈥檛 victimless.

For anyone who has grown up here in the worst years of the bombing campaign, of security gates and body searches, it really feels as though Belfast has got its centre back.

So, to wake on the morning of 21 December to news that a gang has stolen £26.5 million from the Northern Bank, right next to the city hall is to experience a special category of shock.

There is, it is true, a moment when it is hard to see past the sheer audacity of it: the biggest robbery at that time in British criminal history, carried out almost in full view of Christmas shoppers (if they had only understood what they were looking at), on one of the busiest shopping nights of the year. A friend of mine tells me she wishes she had done it. Very quickly, though, details emerge of the kidnapping of the families of two Northern Bank employees, and of the terrifying ordeal one of those family members in particular was made to suffer. The robbery may have been big, it may have been in one sense clever, but it certainly wasn’t victimless.

Missing money and a political crisis

There are certain things you know living here. One is that if the police don’t get wind of large numbers of armed men moving about the city, the paramilitaries will. Unless of course the large numbers of armed men and the paramilitaries are one and the same.

The robbers appear to have been even more expert than the police themselves.

Before the day is out the IRA is being blamed, but to prove anything police have first to find the money, or something vaguely resembling evidence. And that is the problem: the robbers appear to have been even more expert than the police themselves in scene-of-crime forensics, endlessly bleaching, removing all trace of themselves as they went.

As the Christmas decorations come down and the police appear to be no nearer to making a breakthrough, the robbery sparks a full-blown political crisis.

The search for the missing cash meanwhile goes from one end of the island to the other, from a money-lender’s wheelie bin to the offices of an advisor to the Irish government. And yet the only money that can conclusively be linked to the robbery turns up – almost literally – in the police’s own backyard.

The end to the Troubles?

For a few months a lid seems to have been lifted not just on the conduct of paramilitary organisations, but on the whole way we conduct politics on this island. Then, in July 2005, comes an unprecedented statement from the IRA, calling on its members to dump arms and to assist in the development of purely democratic programmes.

For many people – to answer the question my mum asked at the time of the 1994 ceasefire – that statement really is it, the definitive end to our Troubles. The furore over the Northern Bank robbery already seems a distant memory.

As the first anniversary of the heist comes into view, though, police make an arrest that brings the story right back to where it started, with a knock at a door, a Belfast suburb, and a young bank official, , getting up to answer.

Chris Ward was the only man charged with the £26.5m Northern Bank robbery, in December 2004. At trial, he was found not guilty. .

The Northern Bank Job on Radio 4: Through dramatised court testimonies, new interviews and archive, Belfast writer Glenn Patterson takes us into the unfolding story of a meticulously planned heist and its chaotic aftermath.

Essential podcast listening on Radio 4

-

![]()

Intrigue: Mayday

Mayday: When James Le Mesurier fell to his death he left behind a tangle of truths and lies.

-

![]()

The Battersea Poltergeist

A paranormal cold case, re-investigated through a thrilling blend of drama and documentary.

-

![]()

Fortunately... With Fi and Jane

Jane Garvey and Fi Glover share stories they probably shouldn't with guests from Radio, TV and podcasting.

-

![]()

Grounded with Louis Theroux

Stuck at home, Louis is using the lockdown to track down some high-profile people he's been longing to talk to.