Lady Killers ÔÇô The lives and crimes of eight 19th-century women

In 19th-century Britain and North America, women were regarded as the ‘weaker sex’. Their ability to bear children gave rise to a feminine ideal based on marriage and motherhood, while their subservient status to men was reinforced through law.

In this context, women who killed were viewed as having committed a double offence: against the laws of society, and against the laws of nature. Yet such ideals could also work in women’s favour, as those who presented themselves as delicate damsels could convince male juries that they were incapable of murder, while pleas of insanity – especially those rooted in female biology – were increasingly accepted by the courts.

At the same time, the relative rarity of murderesses, the Victorian love of sensation and the rise of modern media combined to produce an abundance of historical evidence which provides a window into the lives, ambitions and predicaments of women from across the social spectrum.

The eight murderesses featured here include those who continue to be household names today, and those long since forgotten. Together, they provide a representative portrayal of female living, and killing, in the Victorian age.

Florence Bravo

During the 19th century, married women in England and Wales began to acquire new, limited, rights over their children, property and person. Unfortunately, they provided little, if any, relief in cases of marital discord. Moreover, civil divorce, introduced in 1857, was available only to those who could afford it and to wives who were victims of “aggravated” adultery (that is, adultery accompanied by violence, incest, rape or sodomy).

Florence Bravo (née Campbell) was particularly unlucky in love. Her first husband, an alcoholic, drank himself to death, though he left her a sizeable fortune. She found solace in the arms of Dr James Manby Gully, but he was already married. In 1875, Florence married Charles Bravo, a handsome barrister, who seemed to offer the prospect of a respectable and lasting relationship. However, Charles only married Florence for her money, and when he found out it was tied up in trusts and out of his reach, he began to criticise her lavish lifestyle, torment her with comments about her previous affair with Dr Gully, and force her to have sex with him when she was recovering from miscarriages. On 21 April 1876, Charles died having been poisoned with antimony.

Did Florence murder Charles? The jury at the inquest into Charles’s death remained doubtful. However, during the proceedings of that inquiry the details of Florence’s affair and marital life were exposed to the public. Under a cloud of suspicion and shame, Florence retreated to Southsea where she lived under an assumed name and died of alcohol poisoning in 1878.

Madeleine Smith

For the wealthier classes in 19th-century Britain, marriages were primarily social and economic alliances. Women seldom married men of a lower socio-economic group and pre-marital sex was frowned upon because husbands wanted to ensure that any children from the marriage who would inherit their wealth were biologically theirs.

In the Spring of 1855, Madeleine Smith, a young lady from a wealthy Glaswegian family, risked everything when she began an affair with Pierre Emile L’Angelier, a warehouse clerk from Jersey who was 12 years her senior. For nearly two years, Madeleine managed to keep the affair hidden from her family and friends. However, a record of their affection, intentions of marriage, and sexual activities was created in the letters that passed between them. The affair came to an end in early 1857, when Madeleine accepted a marriage proposal from William Minnoch, a suitor from a prominent family who had her parents’ approval. When Emile threatened to show Madeleine’s letters to her father, Madeleine panicked, and invited Emile to a secret rendezvous. On 23 March 1857, Emile died, having been poisoned with arsenic.

When Madeleine’s letters were discovered among Emile’s possessions, she was arrested and charged with murder. Details of her relationship with Emile shocked and entertained the public when the letters were read out during her trial in early July 1857. But the jury returned a verdict of “not proven” and Madeleine was left with a choice: likely social ostracism in Glasgow, or to move away and remake herself. She chose the latter.

Esther Lack

The killing of children by their mothers had long been regarded as a heinous crime. However, in early 19th-century England, the increased emphasis on domesticity and feminine ideals drew attention to the perceived biological vulnerability of women. From the 1820s, doctors began to link the violent behaviour of some mothers to the rigours of childbirth and breastfeeding, and to diagnose such women with “puerperal insanity”. By the 1850s and 1860s, mothers accused of murdering their children often used the defence of insanity.

From the 1820s, doctors began to link the violent behaviour of some mothers to the rigours of childbirth and breastfeeding, and to diagnose such women with ÔÇťpuerperal insanityÔÇŁ.

From childhood, Esther Lack (née Hoare) had suffered from both physical and mental illness. In 1842, she married John Lack, a night watchman, and the couple moved to a small tenement in Skin Market Place, Bankside, London. By 1862, Esther had given birth to 12 children, including triplets, but only six had survived. Her health had also deteriorated, and she suffered from poor eyesight, severe headaches, epileptic fits and leg ulcers. She needed to go to hospital, but was worried about being separated from her three youngest children.

On 22 August 1865, when John Lack arrived home in the early hours of the morning he found his wife covered in blood and the lifeless bodies of three of his children – Christopher (aged 9), Eliza (4) and Esther (2). During her trial at the Old Bailey much was made of the fact that Esther had recently stopped breastfeeding her two-year-old daughter. She was found not guilty of murder by reason of insanity. Esther was sent to Fisherton House Asylum in Wiltshire where she died just two months later.

Amelia Dyer

From 1834 in England and Wales, unwed mothers were financially responsible for children up to the age of 16. Without family support, such women had few options. Many paid a stranger – a baby farmer – to look after their children. Baby farming was a largely unregulated industry, and while some baby farmers were decent women, others were unscrupulous.

Amelia Dyer (née Hobley) began her career as a baby farmer in Bristol in c.1868. Her use of pseudonyms, frequent change of address, and imprisonment in 1879 for the neglect of children in her care, suggest that she was, from the beginning, one of the worst kinds of baby farmer, who took lump sums of money from parents and disposed of the children as quickly as possible.

The extent of Amelia’s murderous business was revealed in 1896, after she had moved to Reading. Between 30 March and 30 April, the bodies of seven infants were pulled from the River Thames at Caversham Lock. Evidence found with the bodies established a connection to Amelia. A police search of Amelia’s house uncovered receipts for newspaper advertisements, letters from mothers and pawn tickets for baby clothes. Amelia was tried at the Old Bailey on 18 May 1896 for the murder of Doris Marmon, just one of hundreds of babies whom she likely killed over the course of her career. Amelia’s plea of insanity was rejected by the court and she was hanged at Newgate Prison on 10 June 1896.

Mary Ann Cotton

Marriage for working-class women was an economic necessity in 19th-century Britain, as they rarely earned enough to support themselves, let alone any children. For widows, children could be obstacles to the formation of new relationships. Some relief was provided through new life insurance schemes if a spouse had been prudent, and the lives of children could also be insured to pay for a proper funeral if necessary. But such schemes could be exploited for nefarious purposes.

Mary Ann Cotton (née Robson), daughter of a coal miner, was no stranger to misfortune and death. Between 1852, when she married her first husband, and May 1872, when she moved to 13 Front Street, West Auckland, she lost three husbands, six children, four step-children, her mother, her friend, and her lover, all supposedly victims of typhus, typhoid, or some other nasty illness. Several had life insurance policies which paid out to Mary Ann.

On 12 July 1872, Mary Ann’s last remaining step-child, Charles Edward Cotton, died after a short illness. Mary Ann, pregnant with the child of her latest lover, had been openly eager to get rid of him, raising the suspicions of several members of the local community. When a post-mortem revealed that Charles Edward had been poisoned with arsenic, questions were asked about the many other members of her family who had died over the preceding 20 years. Despite her insistence that Charles Edward had accidently ingested the arsenic, Mary Ann was found guilty at her trial and hanged on 24 March 1873. She is widely believed to have been Britain’s first female serial killer, as well as one of the most prolific.

Grace Marks

In 19th-century Britain and North America, domestic service was an expanding area of employment for working-class women. Generally speaking, the pay was low and the work was hard. Most resident servants were not allowed to marry. Ideally, the expanded household would adopt a familial structure and relations with the patriarch at the head. In practice there were strict hierarchies, snobbery and sometimes abuse.

In 1843, Irish immigrant Grace Marks was hired as a servant in the household of Thomas Kinnear, a farmer, who resided at Richmond Hill, Ontario, in Canada. It was, however, a bad situation. Kinnear was sleeping with the housekeeper, Nancy Montgomery, who was also pregnant. And Nancy, who behaved as if she were mistress of the house, quarreled with another servant, James McDermott. Driven by animosity, or greed, or a combination of both, between 28 and 29 July, James, assisted by Grace, murdered both Nancy and Kinnear. The servants then loaded a wagon with valuables and set off to start a new life in the United States. On discovering the bodies, friends of Kinnear gave chase, and on 31 July, McDermott and Grace were arrested at a hotel in Lewiston, New York, and brought back to Toronto to face trial.

Both James and Grace were found guilty of murder and sentenced to death by hanging. James was hanged on 21 November 1843. Grace, on account of her supposed subordinate role in the killings, and her femininity, escaped the noose. She was sent to Kingston Penitentiary to serve a term of life imprisonment. She was released in 1872 and resettled in the United States.

Hannah Mary Tabbs

Recently, historians have worked hard to recover the lives and experiences of African American women in 19th-century America. Often we are reliant on occasions when such women interacted with authority, especially law enforcement, and records were created as a result. However, as well as providing evidence of discrimination and suffering, these records have also drawn attention to the agency of African American women.

Hannah Mary Tabbs (née Hannah Ann Smith), was born and raised in the slaveholding state of Maryland during the antebellum and Civil War period. In 1876, she moved with her husband, John Tabbs, a Civil War veteran and porter, to Philadelphia. Both found jobs in domestic service. While Hannah was obedient and deferential at work in a white household, in her own neighbourhood she had a reputation for being feisty and violent. By 1883, she had begun a turbulent affair with Wakefield Gaines, an African American coachman. On 16 February 1887, a violent argument broke out between Wakefield, Hannah and another man, George Wilson. Wakefield was beaten until presumed dead. His body was cut into chunks and Hannah and George got rid of it.

After Wakefield’s torso was found in a pond, Hannah and George were arrested. While both were charged with murder, Hannah managed to convince the jury that she had merely witnessed the killing of Wakefield by George and had been forced by him to dispose of the torso. George, convicted of second-degree murder, served 12 years’ solitary confinement at Eastern State Penitentiary. Hannah, meanwhile, escaped with a punishment of two years’ imprisonment for being an accessory and was released early on account of her “good behaviour”.

Giving female murderers and witnesses a voice

Insights into the world of the Victorians and their attitudes to the accused.

Lizzie Borden

Despite societal pressure, a small but significant proportion of women in 19th-century Britain and North America did not marry. At a time when wages for working women were low and women’s access to professional careers was effectively prohibited, spinsterhood could be a problem. Unmarried women were often dependent on their families. Securing an inheritance was vital.

Lizzie Borden was born in 1860 in Fall River, a bustling mill town in Massachusetts, US. After her mother’s death in 1863, Lizzie’s father, Andrew Borden, a wealthy property developer, married again. His new wife, Abby, struggled to build a relationship with her stepdaughters. As neither Lizzie nor Emma married, they were dependent on their father for money. Despite his wealth, Andrew forced his family to live frugally. He also gave money to members of Abby’s family and Abby, as Andrew’s wife, stood to inherit his fortune if she outlived him. By 1892, tensions in the household were high.

On 4 August 1892, Lizzie discovered the bodies of her father and stepmother. Both had been killed by multiple blows to their heads with an axe. A lack of suspects and perceived inconsistencies in Lizzie’s account of her activities on that day led to her arrest and trial for murder in June 1893. The all-male jury remained unconvinced of her guilt. After her acquittal, Lizzie and her sister used their inheritance to buy a luxurious residence in Fall River’s most desirable neighbourhood. But her community could not forget and Lizzie remained socially ostracised until her death in 1927.

More from Radio 4

-

![]()

Desert Island Discs - Dr Gwen Adshead

Kirsty Young's castaway is Dr Gwen Adshead, consultant forensic psychotherapist at Broadmoor Hospital.

-

![]()

Desert Island Discs - Professor Sue Black

Kirsty Young interviews Sue Black, professor of Anatomy and Forensic Anthropology at the University of Dundee.

-

![]()

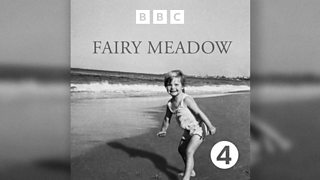

Fairy Meadow

In 1970, three-year-old Cheryl Grimmer was taken from an Australian beach. No-one knows what happened. Fifty years on - can the mystery be solved?

-

![]()

Woman's Hour

Women's voices and women's lives - topical conversations to inform, challenge and inspire.