Who knew? Five eye-opening stories from Composer of the Week

For decades, Composer of the Week has been a popular fixture on ������̳ Radio 3 and before that the Third Programme. For the last 20 years presenter Donald Macleod has proudly continued the programme’s tradition of focussing on the very human stories behind the music of the great composers. The production team recalls five of the most eye-opening stories Donald has shared.

1. An evil omen?

Gustav Mahler liked to write in a composing hut in the Tirolean countryside. It was his creative retreat with just enough there to keep him going, but nothing to distract him. In his hut at Toblach in 1910 he was working on his 10th Symphony despite his superstitious conviction that he would never write more than nine symphonies, the number written by the great Beethoven.

I love to think of what Mahler said when, in the midst of his carefully constructed solitude, an eagle, chasing a crow, burst thought the window, scattering glass across the room. The crow hid under Mahler’s desk. The eagle apparently settled on a chair and glowered a little at the composer before flying away, followed a little later by the crow. Mahler tried to get back to writing, but we know he spoke often of the incident in the remaining months of his life.

It did indeed turn out to be a bad omen. That summer, Mahler received a letter from the architect Walter Gropius which, though addressed to him, was intended for his wife and which made clear that the two were having an affair. Only a few months later, Mahler was dead. He never did complete that final symphony. Was the eagle some kind of messenger?

Discovering Mahler: listen to programmes examining the life and works of Gustav Mahler.

2. Where did I put my head?

If you flick through the contents of Life Magazine dated 28 June 1954 you will find stories on the eruption of the New Zealand volcano, Mount Ngauruhoe and a visit to the USA by the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. And this one: “Haydn’s Skull Is Returned: after theft 145 years ago, body is complete…”

Joseph Haydn died in 1809 and was buried in the Hundsturm cemetery in Vienna. But a few days later, two “admirers” of the composer – Joseph Carl Rosenbaum and Johann Nepomuk Peter – bribed the gravedigger to dig up the coffin and remove the composer’s head. The two men were fascinated by the then supposed “science” of phrenology. When they had duly examined their gruesome trophy, they were delighted to find that the “bump of music” was indeed “fully developed”.

So, when Prince Nikolaus II of Esterhazy got around to having Haydn’s remains dug up so they could be transferred to the family seat at Eisenstadt, he found that the head was missing. He immediately realised who must be responsible, and ordered them to hand over the skull. But they fobbed him off with some other skull they happened to have lying around. This impostor skull was re-buried with the rest of Haydn.

However, the original skull – the one that actually belonged to Haydn – was still at large. After the deaths of the two men who had stolen it, the skull was bequeathed to the Society of the Friends of Music in Vienna, where it would occasionally be brought out.

But in 1932, Prince Paul Esterházy, Nikolaus’s descendant, decided to build Haydn a splendid marble tomb in Eisenstadt. He knew about the real skull and decided to to re-unite it with the rest of Haydn but it took another 22 years until his ambition was finally fulfilled and in June 1954, it was blessed by a Cardinal and placed in a new coffin, thus gaining the composer that coveted slot in Life magazine.

Discovering Haydn: listen to programmes examining the life and works of Joseph Haydn.

3. The long and winding roads...

Composers are often imagined to be creatures whose natural habitat is a study with a desk, a pen and piles of manuscript paper. However, many composers have been great travellers, and it’s often in travel that some of the most interesting stories are found. It’s estimated that Mozart spent about a decade of his not-quite-36 years on tour. We also know that J S Bach walked 250 miles from Arnstadt to Lübeck in order to meet his hero Dietrich Buxtehude. Antonin �ٱ���ř&�������ܳٱ�;�� developed a very keen interest in steam locomotives and could certainly be considered to be the equivalent of a modern-day train spotter.

Two other journeys stick in the mind. Sergei Rachmaninov was working on his First Piano Concerto when news reached him, at the end of October 1917, of Lenin’s overthrow of the Russian Government. He decided to escape with his wife and two girls to Stockholm. They had 500 roubles apiece and could take with them only what they could carry – which in Rachmaninov’s case included a small pile of musical scores. The journey by train was treacherous, but the family finally crossed into Finland, in an open sledge during a blizzard, taking the train first to Helsinki, eventually arriving in Stockholm on Christmas Eve 1917. Rachmaninov never went back to Russia.

Another Russian, �Ѿ������ł���� Weinberg, also had a perilous journey. In 1939, as the Germans advanced into Poland, it became clear that Jewish people were not safe: Weinberg and his sister set off walking, heading east. Weinberg walked all the way to Minsk, a distance of over 300 miles. However, his sister turned back – she was exhausted and her shoes were uncomfortable. Weinberg never saw any of his family again.

Discovering Rachmaninov: listen to programmes examining the life and works of Sergei Rachmaninov.

4. Grinding it out

It’s always fascinating to see where composers gets their inspiration, learning what the origins might have been of some of the most memorable pieces of music.

One of the most remarkable tales on this subject is told by the composer, conductor and friend of Schubert, Franz Lachner. Calling on Schubert one morning in 1826 they decided to share some coffee. Schubert got out an old coffee grinder and began grinding the beans, only to stop suddenly and exclaim “I’ve got it, I’ve got it, you crusty little contraption!” He then picked up the coffee grinder and threw it into the corner, scattering beans everywhere. Unconcerned, Schubert then wrote down the "tune" that had come from the coffee grinder, which, according to Lachner, turned out to be one of his most famous works, his Death and the Maiden quartet.

However, inspiration can be fickle. Harmony Ives, wife of the American composer Charles Ives, recalled that in November 1926 her husband "came downstairs one morning with tears in his eyes, and said he couldn’t seem to compose any more". He was 52, and although he lived for another 28 years, this most original and creative of composers never completed another new work. Ironically, the last piece he did complete, a couple of months before, was called "Sunrise". It turned out to be a sunset instead.

Discovering Schubert: listen to programmes examining the life and works of Franz Schubert.

5. Spontaneous combustion

Those who work in chemistry, and particularly organic chemistry, probably know that the Russian composer Alexander Borodin was a Professor of Chemistry in St Petersburg and spent a career in scientific research. He worked on his compositions in his spare time, which isn’t bad for a man who produced several major works.

It’s perhaps less well-known that Edward Elgar was also a keen chemist, though in more of an amateur tradition. His friend the violinist W H Reed recalled that Elgar used to like to make a concoction from phosphorus which would dry out and then explode as if by spontaneous combustion. One day, while working on his oratorio The Kingdom, he made slightly too much of the material and so shut it in a water butt while he went back to his study to continue writing. A little later there was a mighty explosion, and, according to Reed, “all the dogs of Herefordshire gave tongue.”

Elgar himself reacted with the calm serenity which you can find in the best of his salon music. He lit his pipe and strolled to the bottom of his drive where, when asked by a neighbour if he had heard the mighty bang, replied “Yes, I heard it. Where was it?”

Discovering Elgar: listen to programmes examining the life and works of Edward Elgar.

Composer of the Week is broadcast every weekday at 12pm. A weekly podcast version is available to download. You can find Composer of the Week at ������̳ Sounds.

Composer of the Week on ������̳ Radio 3

-

![]()

Composer of the Week

Donald Macleod offers an informative and accessible guide to composers and their music.

-

![]()

Composers A to Z

Find ������̳ Radio 3 programmes about composers and their works.

-

![]()

Discovering the great composers

Listen to programmes about the lives and works of some of the greatest classical composers.

-

![]()

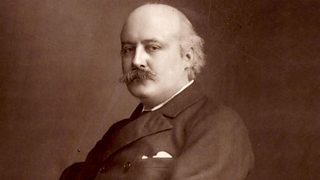

A man out of time – why Parry's music and ideas were at odds with his image...

The composer of Jerusalem was very far from the conservative figure his image suggests.