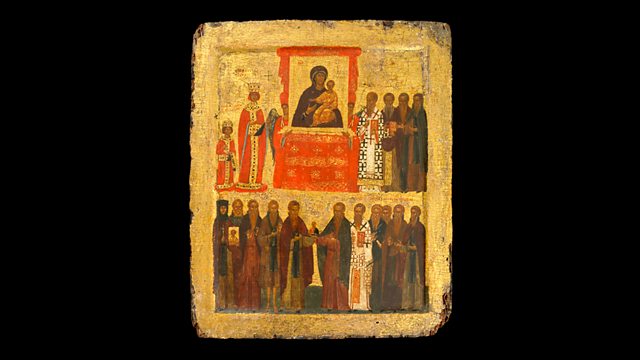

Icon of the Triumph of Orthodoxy

Neil MacGregor's world history as told through objects. Today - an icon celebrating the restoration of holy images at the end a period of religious iconoclasm.

This week Neil MacGregor's world history as told through objects is describing how people expressed devotion and connection with the divine in the 14th and 15th centuries.

Today he is with an icon from Constantinople that looks back in history to celebrate the overthrow of iconoclasm and the restoration of holy images in AD 843 - a moment of triumph for the Orthodox branch of the Christian Church. This icon shows the annual festival of orthodoxy celebrated on the first Sunday of Lent, with historical figures of that time and a famous depiction of the Virgin Mary.

The American artist Bill Viola responds to the icon and describes the special characteristics of religious painting. And the historian Diarmaid MacCulloch describes the often troubled relationship between the Church and the images it has produced.

Producer: Anthony Denselow

Last on

![]()

Discover more programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects about religion

About this object

Location: Istanbul, Turkey

Culture: Middle Ages

Period: 1400

Material: Paint and Wood

��

This icon commemorates the Triumph of Orthodoxy, a pivotal moment in Byzantine history. It depicts the Empress Theodora, dressed in red, who restored the use of images in religious worship in AD 843. For over a century previously, emperors had forbidden images of Christ, the Virgin Mary and the Saints. Empress Theodora is accompanied by her son and saints associated with the veneration of icons. This icon was made over 500 years after this event, when the shrunken Byzantine Empire was under the threat of invasion by the Ottoman Turks.

What role did icons play in the Byzantine Empire?

The Byzantine Empire was the eastern Greek-speaking half of the Roman Empire. While the last Roman emperor was deposed in AD 476, the Byzantine Empire continued until 1453. What we think of as the Eastern Orthodox Church was created largely within the Byzantine Empire, and the veneration of icons is part of its legacy. The painted icon on a flat wooden panel, that we are familiar with today, has its origins in the Byzantine Empire. Icons are still used in the Eastern Orthodox Church to focus worshippers' prayers on a particular saint or subject.

Did you know?

- The most famous Byzantine icon shows the Virgin and Child and is supposedly painted from life by St Luke.

A Vision of paradise

By Robin Cormack, Professor Emeritus in the History of Art, Courtauld Institute of Art, London

��

The Triumph of Orthodoxy icon is not a simple work of art. It is a symbolic proclamation of the power of images.

In the first centuries of Christianity, converts expected the imminent end of the world and their personal entry into paradise. The production of art was consequently an irrelevance for them. But from the third century onwards this immediate anticipation receded. The investment in permanent churches for communal worship and the dedication of monuments to record the death of charismatic saints or places of Christian witness, like the tomb of Christ at Jerusalem, stimulated the development of art to embellish places of pilgrimage and pious devotion.

Yet some groups in the church strongly disapproved of this conspicuous promotion of art. In response Pope Gregory the Great, around AD 600, defended imagery as useful for teaching the Christian message to the illiterate and for helping the faithful towards the contemplation of God. Despite church support for art along the same lines in Byzantium, all Christian images were aggressively banned there during the long period known as Iconoclasm from AD 730 to 843, leading to the disappearance of figurative art in the eastern Mediterranean at the very moment when Islam, a religion without images, emerged.

The Byzantine iconoclasts ultimately failed in their attempt to limit the scope of Christian art to the representation of the cross. Instead the idea that since God became man on earth, it was proper to show Jesus Christ, his mother Mary and the saints in art as objects of veneration finally prevailed as Orthodox church doctrine. Iconoclasm was declared to be a wicked heresy. This was argued theologically and also as a matter of practice by stating that St Luke as well as writing a Gospel was an artist who had portrayed the Virgin and Child from life and that his actual icons still existed.

The Triumph of Orthodoxy icon shows the continuing strength of feeling at Constantinople in the fourteenth century about the necessity of images in the Orthodox church. At its centre is shown one of the icons of the Virgin and Christ painted by St Luke and preserved in Constantinople. It is shown venerated by the theologians, monks and emperor and empress who defeated the iconoclasts.

From the ninth century, figurative images of Christian saints and stories decorate domes, walls and portable panels, all called icons – representations or symbols – and became the agreed essential support of prayer and worship at home and at church, at times of both joy and sorrow.

Orthodox Christian artists were required to produce icons to function for centuries, the best being both technically superb (painted in egg tempera or made in durable materials like gold, silver or ivory) and in a style avoiding all ephemeral fashions. Icons are made to be carried in processions accompanied by incense and chanting, kissed with emotion, and are the objects of contemplation, prayer and meditation. As things of beauty and symbols of eternal truths, icons transform their space into a vision of paradise.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Tue 6 Jul 2010 09:45������̳ Radio 4 FM

- Tue 6 Jul 2010 19:45������̳ Radio 4

- Wed 7 Jul 2010 00:30������̳ Radio 4

- Tue 13 Jul 2021 13:45������̳ Radio 4 FM

Featured in...

![]()

Religion—A History of the World in 100 Objects

A History of the World in 100 Objects - objects related to religion.

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects