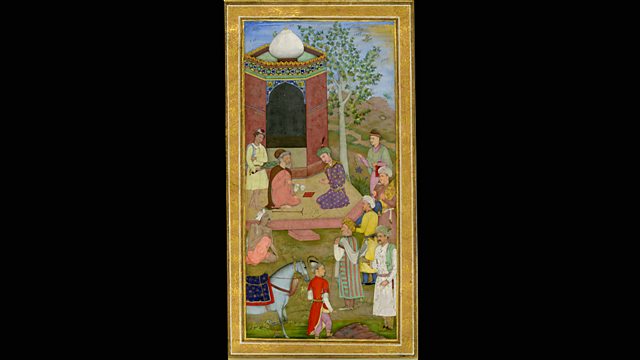

Miniature of a Mughal Prince

Neil MacGregor is exploring the co-existence of faiths across the globe around 400 years ago. Today, he is with a miniature painting from Mughal India.

This week Neil MacGregor's history of the world is looking at the co-existence of faiths - peaceful or otherwise - across the globe around 400 years ago. Today he is in one of the great Islamic empires of the 16th and 17th centuries - in Mughal India. He tells the story of the Mughal rulers and their relationship with Hindu India through a miniature painting (dated around 1610) that shows an encounter between a noble man and a holy man. Neil describes an early mood of religious tolerance and the development of this exquisite art form. Asok Kumar Das discusses the function of miniature painting in India and the historian Aman Nath reflects on encounters between holy men and men of political power throughout Indian history.

Producer: Anthony Denselow

Last on

![]()

Discover more programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects about art.

About this object

Location: South Asia

Culture: Islam

Period: About 1610

Material: Paint and Paper

��

This miniature painting depicts an Indian Mughal prince and his attendants meeting an aged Muslim holy man in a garden. A scantily-clad worshipper kneels in front of the holy man. His lack of clothes indicates that he has rejected the trappings of everyday life. The miniature was probably painted under the reign of the Mughal Emperor Jahangir, who was known to have often visited both Hindu and Muslim holy men as he travelled around his empire.

Who were the Mughals?

The Mughals were a Sunni Islamic dynasty that ruled Northern and Central India from 1526 to 1858. The early Mughal emperors successfully ruled the largely non-Muslim population of their empire by encouraging a culture of religious tolerance. Jahangir and his father Akbar promoted Hindus and Shi'ite Muslims to prominent roles in government and allowed people to worship freely. The art of miniature painting, which combined elements from Iran, Central Asia and India, was practiced by both Hindus and Muslims alike and encapsulates this multicultural society.

Did you know?

- The first Mughal emperor, Babur, conquered northern India in AD 1526 and was descended from Genghis Khan and Tamerlane.

A demonstration of faith

By Aman Nath, historian

��

Born in India and you know being part of its culture, civilisation and history, it seems to me a very normal scene for us. You know, even today not much has changed because people who are in a position of power go and visit holy people. I mean we have an election at hand and all the politicians go visiting all the holy people, perhaps for the wrong reasons too, but in the painting that we are talking about it’s actually faith. It looks more like faith than a demonstration of faith to me. Because a prince who has other priorities as a young man is born, is conditioned to think that if you get the blessings of holy people that all will be well in your reign. And the fact that he is not coerced and, you know, he just visits a Sufi saint and he bends his neck, and that I think is the key thing in the painting. Because a man of greater wealth, power, ambition, sits on the ground and kneels before a man who has sacrificed everything.

I’m not really saying it’s religious sanction, I think it’s just faith, you know, let me give you an example. If a fakir, who is dressed in nothing, arrives at a Mughal court, you know at the wealthiest court, let’s say, of Shah Jahan or somebody who’s bedecked in jewels, the natural reaction of the Emperor would be to stand up and receive him. Whereas if an ambassador came from King James or the Persian ambassador and so on, he was not obliged to stand up because all kinds of thoughts about hierarchy and position would say should I stand up?’ and we had nobles who wore anklets, who were given anklets of gold and jewels to go on their feet, so when somebody with an anklet walked up to an Emperor or to Maharaja he looked and saw, ok this is a man of some status, I should stand up.

So these kinds of conditions do not come in when you’re talking about holy men, because they are fakirs, and if you look at Churchill and Gandhi in 1931, you know, Churchill actually made Gandhi very famous by calling him the seditious fakir, walking half naked when he went to meet the Emperor, and 1931 is recent memory. So the same thing continues, and he was asked, don’t you think you’re inappropriately dressed to meet his majesty? He said, and I think it’s very well known, he said ‘I think he’s dressed enough for the two of us’, but, I mean, jokes aside, what he was saying was that we don’t need this to demonstrate who we are and what we are.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Tue 28 Sep 2010 09:45������̳ Radio 4 FM

- Tue 28 Sep 2010 19:45������̳ Radio 4

- Wed 29 Sep 2010 00:30������̳ Radio 4

- Tue 7 Sep 2021 13:45������̳ Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Art—A History of the World in 100 Objects

A History of the World in 100 Objects - objects related to Art.

![]()

The Art of Monarchy - Behind the Royal Image

Art of Monarchy - Behind the Royal Image - Highlights from the Radio 4 collections

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects