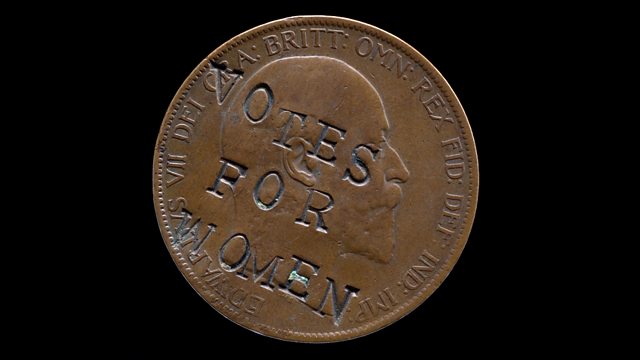

Suffragette-defaced penny

Neil MacGregor's world history as told through things arrives in the 20th century. Today he chooses a British penny coin defaced by suffragettes with the words "Votes for women".

Neil MacGregor's world history told through objects from the British Museum in London. The objects he has chosen this week have reflected on mass production and mass consumption in the 19th century. Today' he is with the first object from the 20th century, a coin that leads Neil to consider the rise of mass political engagement in Britain and the dramatic emergence of suffragette power. It's a penny coin from 1903 on which the image of King Edward V11 has been stamped with the words "Votes for Women". The programme explores the rise of women's suffrage and the implications of the notorious suffragette protests. The human rights lawyer and reformer Helena Kennedy and the artist Felicity Powell react to this defaced penny coin.

Producer: Anthony Denselow

Last on

More episodes

Next

You are at the last episode

![]()

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

About this object

Location: England

Culture: The Modern World

Period: 1903

Material: Metal

��

This penny, struck in 1903, has been defaced with the slogan 'Votes for Women' over the portrait of King Edward VII. At the start of Edward VII's reign women, along with the poor and criminals, were denied the right to vote. Mutilating coins was one of the methods suffragettes used to spread their message of universal suffrage to a wide audience. Pennies were used by all sections of society and were so small a denomination they were rarely recalled by the Bank.

How else did the Suffragettes campaign for votes for women?

Suffragette derives from the word suffrage meaning the right to vote. As well as conventional campaigning, the suffragettes also attacked museums, famously slashing The Rokeby Venus, a painting in the National Gallery, in 1914. They also smashed a mummy case in the British Museum. In 1918 the Representation of the People Act gave women over the age of 30 the right to vote but it was not until 1928 that women were given the same voting rights as men.

Did you know?

- Suffragette was a word first used by the Daily Mail newspaper as a derogatory term for the movement for women's suffrage.

Past sacrifices in my name

By Catherine Eagleton, curator, British Museum

When I started working at the British Museum, I had a good look at the objects in the part of the collection that I look after. One in particular caught my eye: the Suffragette penny. It is stored in a cabinet with lots of other coins that have been re-engraved or have had messages stamped on them; everything from adverts for soap powder to messages of love. More interesting to me, though, were the coins that were marked with political messages, like this one.A couple of years later, curators at the Museum were asked to suggest objects that should be part of a touring exhibition called Treasures of the World's Cultures, and I immediately suggested this coin. Writing the exhibition text meant that I had to research the women's suffrage movement, and find out more about some of the things that women and men had done that enabled me, 100 years later, to turn up and put a cross in a box on election day. I have always treasured my right to vote, but despite that I hadn't until then thought all that much about the campaigns that led to women getting equal voting rights to men, or the suffering that had been involved.

A particularly inspiring moment came last year, when I spent some time with a group of refugee and asylum seeker women as part of the Museum’s Talking Objects project. Hearing them talking about their experiences, and discussing with them the differences in the treatment of women in the countries where each of us had lived, made me think about the Suffragette penny in new ways.

Now, as well as being an amazing object - the ordinary made extraordinary by the message stamped on it - this coin reminds me of the past sacrifices and campaigns made in my name, and also the work that there still is to do.

A wonderful way to make a statement

By Helena Kennedy, human rights lawyer

��

Looking at this coin it is extraordinary to just imagine how they were thinking ways of affronting the public or drawing the public’s attention to what they wanted and here you stamped on to this copper coin ‘votes for women’, on the very face of the King.

It was an affront, it would have been so shocking to society at that time; it would be treasonous. That act was in itself seen as treachery and yet of course people would be handling coins in their purses and in their pockets and would suddenly see this invocation, this demand for a right, for an entitlement and I think it was quite an inventive thing to do.

Of course stamping a coin was against the law. Defacing coinage is against the law so there is that issue of whether it’s ethical to break the law in certain circumstances. Is it ethical to do it and my argument would be that there are some times when in pursuit of human rights it’s the only thing that people can do. As a lawyer I’m not supposed to say that but I think there are occasions when the general public would agree, that somehow one has to stand up to be counted.

There have been other examples of where civil disobedience has brought success. Gandhi was one of the great representatives of this, of a peaceful opposition and he created great change in his nation as a result. These women were so courageous because they were often so hurt and harmed in the process and they were fearful. But they overcame their fear because of their belief that this was right, that women should be treated equal to men and if we wanted to have a society where all voices were heard then there had to be an extension of the franchise.

This penny is just such a simple and tiny object and it says so much, so much about what we are wanting, about seeking equality for women and about how into the hands of those who had power and influence there was this small but huge demand, votes for women.

I get a really visceral thrill from this object. There is something so extraordinary about it, the idea that this tiny everyday item, a copper, a penny in your pocket and that some powerful politician, some banker, some eminent personage of those times would have taken from his pocket a penny to pay for something and there was the message, votes for women. To hold it gives you a sense of connection to the suffragettes. It’s wonderful and it’s those things from history, those objects that just take us back to a period, to a moment, to a wonderful imaginative way of making a political statement.

Transcript

Broadcasts

- Fri 15 Oct 2010 09:45������̳ Radio 4 FM

- Fri 15 Oct 2010 19:45������̳ Radio 4

- Sat 16 Oct 2010 00:30������̳ Radio 4

- Fri 12 Nov 2021 13:45������̳ Radio 4

Featured in...

![]()

Leaders and Government—A History of the World in 100 Objects

More programmes from A History of the World in 100 Objects related to leaders & government

Podcast

-

![]()

A History of the World in 100 Objects

Director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, retells humanity's history through objects