Stop the silent suffering of Somali girls

Mohammed A. Gaas

Deputy Country Director, Somalia

Tagged with:

A girl pictured in a produce market in Barawe, Somalia

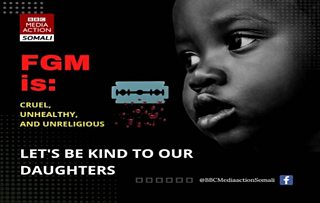

UN figures indicate that over 90% of girls and women in Somalia have been subject to female genital mutilation (FGM). Discussions over FGM remain a taboo in many places in Somalia and the devastating health ramifications – including pain, bleeding, permanent disability, trauma and even death - remain prevalent.

The most commonly cited reasons for carrying out this harmful practice include cultural norms related to social acceptance, religious misconception related to cleanliness – including the belief that those who have not been cut are unclean or unworthy, and the preservation of virginity before marriage, while some believe that it is a rite of passage to adulthood.

Whatever the reasons given, FGM is a physical assault conducted on girls too young to consent, and a violation of their rights.

łÉČËÂŰĚł Media Action seeks to support people in understanding their rights. The level of FGM we are witnessing in Somalia is significantly alarming and I believe needs to be addressed from the grassroots to national level.

With support from German aid agency GIZ, we are producing radio magazine programmes broadcasting in all member states of Somalia through our local partner stations, to share trusted information about the harm caused by FGM and share the perspectives of health experts, religious leaders and survivors.

These łÉČËÂŰĚł Media Action-produced programmes include voices from all member states of Somalia, and all Somali dialects including ‘the Mai’, which is spoken in the South West state of Somalia. This helps builds a sense of belonging for all Somalis in relation to the programme, which is rebroadcast by seven local radio partner stations across the federal republic of Somalia and Somaliland.

The truth about FGM

The World Health Organization has created four medical classifications of FGM; level 3 is the most extreme and is also most prevalent in Somalia and Somaliland.

All classifications of FGM can cause complications at childbirth and increases risk of newborn death; other complications include fistula, bleeding, chronic pelvic infections, urinary problems and infections. FGM is often carried out under unsanitary and primitive conditions without anaesthetic, which causes severe pain, bleeding and swelling that may prevent passing urine and faeces.

We met Farhiya Abdi Ali when she featured on our weekly radio programme, Tusmada Nolosha (Lifeline). She described going through the painful FGM process:

"I am one of the many girls [who] encountered a lot of problems such as blockage of menstruation. I was taken to hospital and the only option was to open me by removing the stitches. If not opened [it] could have caused a bigger problem."

It is often believed that FGM can prevent girls from becoming pregnant. We featured Mrs Foosia Muse, a midwife at Hargiesa group hospital, in our social media clips about FGM, who clarified this is not the case.

"They believe that if the girl is stitched, she cannot be touched. But they are touched and some are brought to us stitched and pregnant. The small passage that you make for the girl for urination is the same passage that the baby enters the womb."

Our campaign in Somalia aims to reduce the incidence of FGM by connecting with people's emotions

Laws and religious perspectives

In our formative research, we also found that some mothers believed that FGM is a religious act, that a family that does not practice FGM will face stigma and the girl will be considered to be a non-Muslim.

"FGM is a huge part of the religion because it an act of worship, and a family that doesn't perform FGM on their daughters will be discriminated within the community," said a mother in Garowe, whose daughter has undergone FGM.

To help counter this, in Somaliland, the government introduced a fatwa which bans the practice of female genital mutilation in the country and vowed to punish perpetrators. The fatwa, issued by the Ministry of Endowment and Religious Affairs, pledges punishment for those who carry out FGM, and asks for compensation for FGM victims.

However, it does not clarify whether this compensation will be paid by the government or by those who violate the ban, and appears to be restricted to only the most extreme form of the practice.

This fatwa is so far only in writing. The practice of FGM has not stopped and as yet, there are no reports of fines, punishments or compensation given.

But Islamic clergy are divided on zero tolerance of FGM. Although they all agree that it is unreligious, most of them still support the ‘Sunna’, or Level 1 FGM practice; some see that FGM is part of religion, in the same way that prayer is.

Yet the Islamic religion prohibits anything that is harmful to people’s lives, and views differ among religious leaders. When we spoke with Sheikh Abdikadir Deria Adan on our programme, he said:

"It is not compulsory, as indicated in the Prophet’s teaching; nowhere have the wives of the Prophet spoken of or practiced FGM."

We realised that to reach zero tolerance for FGM, raising awareness on the harm caused by the practice was imperative. We also understood that religious leaders with academic, scientific and medical knowledge would be more likely to understand and help convey the risks.

Killing one to save thousands

In our radio drama, we created two characters who were sisters - Qamar and Amina - who hold contrasting views on FGM. In the storyline both Qamar and Amina have daughters who are of age for the practice. Qamar was preparing her two daughters for FGM, and she tried to convince her sister to bring her daughter for the procedure, too.

Amina was hesitant and seeks advice from her friend, a qualified nurse. The two of them tried hard to stop Qamar, who believed in the traditional myths, but their efforts failed. Qamar believed that as FGM was conducted on her great grandmother, her grandmother, her mother and herself, there was no way she was going to break the cultural chain.

Qamar went ahead and had FGM performed on her two daughters. As the drama progresses, listeners hear how the procedure on one of her daughters, Yasmin, goes wrong and they were unable to stop the bleeding. The women take Yasmin to hospital in an effort to save her life, but she sadly dies.

We know that drama has great power to help address cultural sensitivities and taboo topics like this by building empathy with characters based on real-life examples. Our research showed that stories and characters can help listeners to reflect on their own lives in a less direct way, and challenge entrenched gender norms.

"The death of the girl in the drama made me sad… this ending of the story can also be a lesson to mothers who are thinking of making their daughters undergo FGM," a young woman in Kismayo, who herself has undergone FGM, told us.

We hope that the death of Yasmin’s character in our radio drama will help save the lives of thousands of Somali girls.

--

Mohammed Gaas is Deputy Country Director for łÉČËÂŰĚł Media Action Somalia

Learn more about our work in Somalia here.