Putting audiences at the heart of VR

Tim Fiennes

Head of Audience Research, Emerging Technology

Tagged with:

This blog is about audience research into VR usage in homes across the UK, led by Dr Neil Stevenson at Ipsos Connect and Tim Fiennes at the │╔╚╦┬█╠│. It discusses why they did the research, what they did, and what they found. The findings cover how mainstream audiences currently regard VR, their first reactions to experiencing VR, what types of content resonate and what has impact. It then covers the key challenges the industry must overcome if VR is to become a mainstream media habit, with some considerations for VR practitioners.

Virtual Reality (VR) has certainly been having a moment, with leading pundits forecasting billions of dollars of revenue, the distribution of hundreds of millions of headsets, and the fundamental disruption of audiences’ media habits.

For those who’ve experienced it, the hype is understandable and it’s not without foundation. Work coming out of the Immersive Labs in Oxford, Stanford and UCL suggests there is significant potential for VR to have profound positive social impact by telling stories in immersive and memorable ways.

But we need to pause for a second. A recent observed that ‘enthusiastic reactions to VR at trade fairs or at industry conferences, based on a few minutes of usage, may not convert into mass market demand.’

Most of the content created to date has been driven by the promise of the technology and pushing the vanguard of what is possible. Whilst the experiences created have left many with their jaws on the floor, they have largely not been driven by what works for the non-gaming mainstream audiences – of which there is little knowledge. An found that 60% of participants felt that VR was mainly for gaming and 46% of participants agreed that they couldn’t see a practical use for people like them.

For the │╔╚╦┬█╠│, as a public service broadcaster that reaches 95% of the UK population each week, the question over mass adoption is crucial. And, as younger audiences move away from traditional media, the │╔╚╦┬█╠│ must ensure it has the expertise in new mediums like VR to continue providing them with world-class public service content.

Having pioneered mass market story-telling mediums since 1922, the │╔╚╦┬█╠│ wants to put the same audience-centric approach into the development of VR. To help start this process, we partnered with to better understand what people want out of VR entertainment experiences, how VR is experienced in the home, and what we can learn about the new grammar of storytelling in VR.

We’re sharing these insights so the wider industry can benefit from what we’ve learnt, in order to help improve the experience for everyone.

What we did

We undertook a research programme into VR encompassing market sizing, a mix of existing ‘media needs’ research and a longitudinal ethnographic study. As part of that we recruited teens and adults from across the UK who were interested in VR but had little experience with it. We gave them each a mid-range mobile VR headset for three months.

For the first few weeks we asked participants to play with the hardware every day, discovering VR experiences themselves, and trying pieces we suggested, which we had previously researched and found to be of superior quality.

For the following 12 weeks, we left the hardware with participants to observe how VR would fit into their daily lives in the longer-term.

Participants also joined an online community to talk about their experiences. We visited them in their homes in the first two weeks, and interviewed them at weeks 8 and 14, part way through and at the end of the study.

What we found

There was a huge amount of insight coming out of this study that we’ve tried to summarise in this post. We figured the best way to do this was to share the insights we gathered in the order they came to us....

- What did audiences think about VR before they’d actually tried it?

- How did participants react to their first experience?

- What content were participants drawn to?

- What content resonated?

- What are the key challenges to overcome for VR to become mainstream?

So, what did our participants think about VR before they’d actually tried it?

As you can see from the video there was a wide variety of expectations.

Those with prior experience of basic entry-level mobile VR expected to be underwhelmed; others expected VR to be a futuristic, shiny technology, but were not entirely sure of its sophistication. Unsurprisingly many associated it with gaming. A few were concerned about the experiences they were about to have – they had heard stories of getting nauseous, they didn’t want to look silly in front of friends and family – or indeed, get pranked by them!

In summary, new-comers to VR are unsure about what to expect and about the type of experiences they want to have. But they are excited, and their first experience didn’t disappoint....

How did participants react to their first experience?

Many of you will have seen the videos on YouTube of first encounters with VR – the elderly grandmother gripping her armchair for dear life and screaming (for joy?) as she is thrown about on a rollercoaster.

We found our participants were equally enthralled and delighted. Their initial – fairly low – expectations were far outstripped in terms of the quality of the experience and the very nature of being immersed in virtual reality.

However, this in itself presents a nuanced marketing challenge. The industry has difficulty communicating what VR experiences are actually like. Given the wide variety of technology which can determine the nature and quality of experience, setting the right level of expectation for audiences such that they don’t come away underwhelmed is tricky.

What content were participants initially drawn to?

Generally participants wanted to get straight to experiences designed to get your blood pumping, things like horror, rollercoasters and other extreme experiences that had some novelty value.

What they were not doing was discovering a wide variety of other experiences available to them (more on that later).

We found that when we suggested particular pieces of content, the appeal of VR can go far beyond the novel and extreme, and that audiences can have profound experiences.

What impact did the VR experiences have on participants?

Participants loved VR which allowed you to:

- walk in someone else’s shoes to better understand the world (e.g. experiencing what it’s like to lose your sight – Notes on Blindness).

- experience something you wouldn’t normally do (e.g. sky-diving – although the novelty factor wore off quickly so it’s likely you’d watch these sorts of things a small number of times).

- learn effectively (e.g. become microscopic and travel through the body to learn about anatomy – like the The Body VR);

- remove all distraction, enabling focus on activities like relaxation.

This last type of experience threw out a few surprises. Our participants frequently came back to watching traditional 2-D widescreen content in a virtual cinema – i.e. watching traditional content on ‘the biggest screen in the house’. This was everything from long-form scripted content from popular VOD providers through to music videos on YouTube.

We know from broader media behaviour research that audiences will tend to seek out the best screen available when watching long-form video; however, whether a virtual big screen counts ‘as the best screen available’ given the resolution challenges devices currently have is questionable – it would certainly appear the largest though.

Our emerging hypothesis is that headsets provide audiences with a rare opportunity to engage with content utterly free from distraction. The rise of the smartphone being rarely away from one’s side means that it can often be challenging for audiences to be fully immersed in any kind of activity. A recent from Facebook found that 94% of US consumers kept a smartphone to hand when watching TV. Headsets are a helpful blocker to being distracted by multiple mediums.

What are the other characteristics of content which worked?

From an industry perspective we are still developing the VR story-telling grammar around producing content that works.

By spending time with real people and talking to them about their experiences, we were able to pull out a few key insights into what got them excited and why.

- First, leading the audience on a journey is crucial; experiences without a narrative or goal tended to fall flat – experiences with good story-telling or clear objectives worked well.

- Second, making the most of the unique possibilities of VR. Playing with scale was particularly evident here – for example ‘The Body VR’ shrinking you to a cellular level. Presence and embodiment were also important asthe viewer must feel ‘there’ to be immersed. For example, a Cirque du Soleil experience resonated because the characters made plenty of eye contact with the viewer.

- Third, recognising the risk of cognitive overload: audiences need time to process and understand what is happening around them before being able to follow a narrative. When and where to draw their attention is also fundamentally important.

Experiences that do these things well can blow audiences away and provide a real depth of emotional engagement.

The challenges... (you’re halfway through!)

So, to recap the story so far: audiences are excited, albeit uncertain about the prospect of the new technology; they love having adrenalin-fuelled experiences to begin with, but the novelty can dissipate fast; content with a clear narrative that thinks about the audiences’ experience is crucial; and there’s an opportunity to have a real world impact, and to add value to people’s media routines.

However, we’ve identified four challenging areas that need to be kept in mind when assessing the opportunity VR presents. These are:

- The occasion in which VR will be used.

- The hardware.

- Discovery of content and the current poor user experience.

- The play-out.

Let’s start with the occasion

At the beginning of the research, we asked our participants to use their headset every day for two weeks, completing a range of tasks – seeking out new content, discovering new experiences for themselves and trying out pieces we had suggested. We then left the headsets with them for three months, with no instructions other than to use them if and when they wanted to for the first 7 weeks (i.e. ‘natural usage’), and then 5 weeks of ‘prompted usage’ where we point them to new content. Unsurprisingly over the 7 weeks of ‘natural usage’ their usage declined significantly – with some of them not picking up the headset at all.

We found that often, as described in more detail below, it was just too much of a faff, without enough of a compelling reason to bother. When the headset was used, it tended to be the last media option they turned to, having exhausted TV, their PVR, SVOD, social, gaming.... the rest of the internet(!).

In the words of one participant, “It isn't replacing any of my media habits... it's not as easy: you have to get your phone ready, slot it into the headset and then find something to watch. Normally I can just flick on the TV and watch something instantly!” - Female, 18-44.

There are evidently a range of behavioural barriers to overcome before VR will be habitual. These include:

- Safety and security – some audiences were concerned about being shut-off from what’s happening around them.

- Social norming – some were anxious about feeling stupid in front of friends, or self-conscious about their appearance, hair and make-up.

- Physical space – often audiences weren’t in the right physical situation – sitting down on a sofa after a long day or lying in bed is not conducive to an experience which necessitates turning around and looking behind you.

- Proximity of headset – the headset needs to be conveniently available. Many of us will have hundreds of potentially entertaining distractions in our homes; however, it will tend to be the ones which are the most visible / proximate / easy to engage with which we use. If a headset has been put away on a shelf, in a cupboard, or under a bed, it will not be front of mind.

- Social interaction – for some audiences the insular / individual nature of the experience was off-putting as they preferred connecting with others either digitally or in physical space.

This underlines how the issue of how VR integrates into real lives in the home is of great importance. To overcome this the VR industry needs to give care to making seamless experiences in occasions and settings that are appealing to audiences.

The hardware

If you have decided you want to try some VR, you have found your headset, you’re in a social situation and geographical context you feel safe, you then have the hardware to contend with:

- Often the headsets or the screens of the phone will be dirty – if not cleaned this will significantly diminish the quality of the experience, blurring or obscuring the images.

- The phone must be charged: headsets are often used at the end of the day – after school, college or work, often when the phone is low on power.

Then of course you have to find something to consume

- If you haven’t used your headset for a while, you might forget how to use it – many of our participants found the user interface to be tricky in any case.

- Often the way to navigate around various VR environments differs from app to app – adding to frustration.

- The way in which content is then presented to audiences is a challenge. We found that when our participants were left to discover content themselves, they rarely ventured out of the main app; by themselves they found very little of the high quality content we had given them. Their discovery was mostly limited to gimmicky, adrenalin-focussed and games-orientated experiences, resulting in the novelty factor wearing off quickly.

Audiences need to be exposed to content they might not automatically choose to expand their range of tastes in VR. There is room for intelligent content curation from trusted brands which takes into account the different usage occasions, the different types audience needs, and the goal of expanding VR beyond novelty experiences for audiences.

Once participants had found something to consume, the play-out also caused problems

- Many handsets overheated after 30 or so minutes of usage.

- Variable Wi-Fi quality leading to poor content resolutions and slow download speeds was also limiting.

The content itself

The industry is obviously still learning, but there is a risk of sub-par experiences flooding the market and turning audiences off the idea of VR altogether. We found that much of the content available didn’t add any value over and above consuming the same sort of thing on a TV screen.

A typical comment was “If the content could have been just as easily consumed on a TV screen, why go the effort of watching it immersively?"

For the occasion to be worthwhile, the content must be a special experience that could only have been conveyed in VR and not through any other media.

Thoughts for the future

VR in-home entertainment definitely has massive potential. Headsets will get cheaper and more content will be made. Some content will have substantial impact. These are potentially great things for creators, the public service and the audience.

But when thinking about the audience first, we’ve seen there are some challenges that need to be addressed for VR to realise its potential. For VR to be successful it needs simple, intuitive and consistent interfaces, better curation and content discovery, and a higher supply of quality content which is ‘worth the effort’.

When experiencing problems, audiences don’t particularly care if it’s the hardware, the software, the content or anything in-between that causes a glitch. They just want good experiences and become frustrated when this isn’t possible.

This is exemplified in how our participants responded at the end of the 14 weeks, upon giving the hardware back to us – when asked “Would you now go and buy a VR headset”, they said that with the current mix of content and difficulties with the hardware they would not, but may consider it in the future.

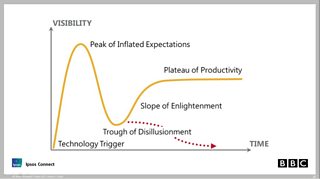

Many of you will recognise this hype curve showing the typical cycle of new technology. But it isn’t a given that all technology becomes mainstream. Think 3DTV.

When thinking about VR in-home entertainment, there could be another trough of disillusionment if we don’t address these challenges.

This is clearly a challenge for the VR industry. Hardware, platforms, and content creators need to be aware of the limitations of technology, but also of the real world context in which audiences will be interacting with VR. This sounds straightforward, but in the fragmented VR landscape, there are a variety of experiences and it’s not clear this is going to be solved automatically.

So we believe there are two calls to action coming out of this work.

First, we need to simplify. We need consistency between the currently fragmented hardware and software experiences. This will enable a more frictionless user experience for all audiences. Consistency and open standards will also provide greater certainty for content creators to produce a breadth of content which is not limited to a small set of costly closed devices.

Second, we must put the audience not just the technology at the heart of our thinking. This will give us a better understanding of audience perceptions, needs, usage occasions and how best to curate. In turn this will enable us to produce more relevant, impactful and memorable content that fits into real people’s lives.

The │╔╚╦┬█╠│ will be continuing to look at VR and how to make amazing immersive content. We’d love to hear from you if you’re thinking about researching this area.

Acknowledgements. Finally, as ever, pulling together work like this takes the dedication of many hard-working people. A big thank you to staff at Ipsos Connect, including but not limited to: Katherine Jameson Armstrong, Dr Neil Stevenson, Elliot Whitehead, Hanna Roe, Anna Hickman, Cecilia Zolo, Hannah Stott, Rhianne Patent, Andaleeb Ali, Alice Ellen, Ian Jarvis, Ellie Rose, Will Shaw, Lucy Kaye, Usman Khawaja; and from the │╔╚╦┬█╠│ , Aleksandra Gojkovic and Jaya Deshpande.