Ten Things You Didn't Know About Tolstoy

1. Tolstoy was a Count

Both Tolstoy’s parents belonged to ancient Russian aristocratic families. His grandfather on his mother’s side, Prince Nikolai Volkonsky, was a member of the court of Catherine the Great and Russian Ambassador to Berlin. His paternal grandfather, Count Ilya Tolstoy, was governor of the city of Kazan (now the capital of Tatarstan), the place enshrined in Russian memory as the location of Ivan the Terrible’s defeat of the Tatar-Mongol Horde.

2. Tolstoy proposed to his wife in code

The Behrs family had three daughters who were close acquaintances of Tolstoy. Though the family wanted him to marry the eldest, Liza, Tolstoy was more attracted to the middle daughter Sofia. Painfully shy yet tormented by his strong sexual desire for Sofia, he struggled to make plain his intentions. Sofia records in her diary that Tolstoy took some chalk and wrote the initial letters of some words on a card table, and asked her to guess the meaning. It was not just two or three letters such as ‘M. M’ for ‘Marry me’, but well over a dozen! Sofia claims that she understood at once. The scene is recreated in Tolstoy’s novel Anna Karenina when Levin proposes to Kitty for the second time.

3. Tolstoy thought Shakespeare was rubbish

Despite reading many of his works and enthusing to Sofia about his enormous dramatic talent, Tolstoy repeatedly published scathing opinions of Shakespeare, saying that he was without genius, a mediocre talent, and that his plays were beneath criticism – ‘I read and re-read the dramas, the comedies, the historical plays, and invariably, each time I experienced the same thing: disgust, boredom, astonishment’. He also said ‘Not only can Shakespeare’s plays not be taken as models of dramatic art, but they do not even conform to the most basic and universally agreed rules of art’. He rated Marlowe as a better dramatist. Ever confident in the rightness of his own views, Tolstoy was never afraid to go against public opinion, even the most widely held beliefs.

4. Tolstoy鈥檚 experience of the Crimean War inspired War and Peace

Tolstoy’s rich, detailed descriptions of military combat in War and Peace are enhanced by his personal experiences. He first served as an artillery officer in the Caucasus in various campaigns to assert Russian imperial rule in the region; he later fought at the siege of Sevastopol during the Crimean War and was promoted to lieutenant for outstanding bravery and courage. Despite appreciating the heightened emotions of battle, he knew a military career was not for him and he resigned his commission soon afterwards. He retained a lifelong fascination for the motivations of military life.

5. Tolstoy gambled away a large part of his family inheritance

As a young man, Tolstoy lived a dissolute lifestyle and gambled extensively, particularly during his time as an army officer. In 1854 he was forced to dismantle and sell for 5,000 roubles the main stately home on the estate inherited from his maternal grandfather at Yasnaya Polyana. By 1855 he had gambled away the whole 5,000 roubles. He settled in a more modest house on the estate and lived there for more than 50 years.

6. Tolstoy made his own shoes

Tolstoy grew increasingly troubled by the privilege of his background and developed an interest in the lifestyle and culture of the peasantry. This extended to making his own shoes in the traditional peasant way out of bast: thin strips of bark from the birch or linden tree. He wasn’t very good at it but he wore them anyway.

7. Tolstoy was excommunicated by the Russian Orthodox Church

Tolstoy believed fervently in the ideals of Christianity, but despised organised religion, which he felt contradicted the teachings of Jesus. After a biting satire of the hypocrisy and corruption of Russian Orthodox Church officials in his last novel, Resurrection, the Church excommunicated him in 1901. The Church, and the Tsarist establishment, hoped that this would make Tolstoy unpopular and would quash his reputation as a critic of the regime. Instead, it served to make him even more famous and admired.

8. Tolstoy was Gandhi鈥檚 Inspiration

Some historians argue that Tolstoy’s essays on peace laid the foundations for modern pacifism. After reading Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God Is Within You, Gandhi was inspired to pursue nonviolent resistance, calling Tolstoy "the greatest apostle of non-violence that the present age has produced". They corresponded for a year until Tolstoy’s death in November 1910, Gandhi later named his second ashram in South Africa ‘the Tolstoy Colony’.

9. Tolstoy was obsessed with sex

Tolstoy had a fraught relation with sex and at times and championed celibacy as a means of moral purity. Despite this, he went on to father 13 children. He lost his virginity to a prostitute and afterwards wrote that he fell to his knees in a wave of self-loathing and guilt. Tolstoy began writing a journal at 18 and set himself very prescriptive goals for self-improvement, one of which was to visit a brothel only twice a month. About the time he began keeping a diary, he wrote that he had contracted venereal disease and underwent treatment in 1847.

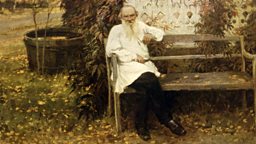

10. Tolstoy鈥檚 death was a major media event

By the time of his old age, Tolstoy was a cultural icon and had followers world-wide who tried to put his views into practice. He fled the family home in 1910, sick of the years of bad relations with his wife, but collapsed at a nearby railway station. The news of the dying celebrity drew huge crowds and news cameras from Pathé, making his death an international news story. More than three thousand people lined the streets to see his coffin carried back to Yasnaya Polyana. As Tolstoy had been excommunicated, there were no religious rites at his burial. Years before the Communists suppressed the Russian Orthodox Church, his was the first civil funeral in Russia.

Authored by Dr Sarah Hudspith, Associate Professor at The University of Leeds