Camels: Kicking up a storm

By Director for Mammals, Lillian Todd-Jones

To reach the outback station where we will film feral camels, cameraman Nick Ball and I drive for two days from the Australian coast. At first this is through vast monocultures: rolling expanses of dull green stretching unbroken to the horizon.

we are zooming on the dead-straight outback highway

Slowly the drizzle subsides, the green turns yellower, then red, and by the end of the journey we are zooming on the dead-straight outback highway. A couple of emus peck near the road. A huge eagle scowls at us from its kill, and the dead bodies of roadkill kangaroos line the hard shoulder.

In Australia there are farms and there are stations. The latter is technically private grazing land but can be so huge that they cover a bigger area than some countries. If you lose your way on a station you may not get found and this unforgiving desert is not a place I would like to be lost.

On our journey we drive through an abandoned mining town. The windows of each house are like eyes staring blankly into the desert.

Soon afterwards we pull up to a small huddle of buildings marking the entrance of our filming station. Unnervingly, it looks like the inhabitants disappeared half a century ago with the miners. The doors are unlocked – creaking as we push them open – and a thick layer of orange dust coats everything inside

“The sand gets everywhere”. Karen the fixer pulls up in a 4x4, wearing wrap-around sunglasses and the kind of chiselled jawline you only get by living half-nomadic in the desert. “We’ll be working amongst the dunes beyond that hill. I’ll show you”.

Outback sand makes the same sound underfoot as fresh snow. The colours are stark and vivid. Orange earth and blue sky are punctuated with white bones from unfortunate ex-animals.

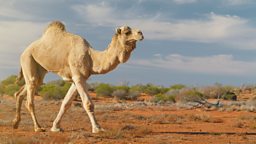

We have come to film camel mating behaviour and I’m thrilled to see how majestic these mammals look amongst the dunes: despite the male blowing gurgling sounds through his dulla, an inflatable sausage-like organ complete with spittle sparkling in the sun. The sack that flaps from his mouth is one of nature’s more unfathomable courtship displays.

But as we film, the weather turns. The sky clouds over and the wind kicks up. We retreat to our kit tent to find that the wind is sweeping under the sides and billowing clouds of sand are covering everything.

The storm builds and we scramble to stash the equipment in sealed cases. As the kit tent strains against the force of the storm I run to the car to grab another case. The toilet tents are dancing manically in the gale. Dust is howling through the thorn bushes. I can’t believe it escalated so quickly! In the distance a wall of darkness is carving across the land, shot with lightning.

I run the case to Nick who stashes the last of our delicate kit into safety. “You guys OK in here?” Karen pokes her head into the tent, unphased. Behind her I see the kitchen gazebo rolling into the desert of its own accord.

The next morning everything is still once again. A flock of budgies wheels around the old well. The spattering of rain that fell in the night has made the stark earth smell sweet. In the kit tent a layer of dust makes it looks like we’ve been gone for a thousand years. But all the gear is safe, and the kitchen tent has been caught and reinstalled.

When we head out, we see that every footprint has been blown away and the dunes are pristine: their perfect beauty reinstated by the brutal, primal force of the desert – and perfect for filming!

How camels make a good first impression

An amorous camel in the Australian outback uses a dulla to try and impress the females.