Three perspectives on Raine Island

Falen Passi

Chairperson Meriam Le (Raine Island Traditional Owners), from Mer (Murray Island), Torres Strait, Queensland

it felt like home

I first visited the island in December 2009, and it felt like home. Many things reminded me of where I come, Mer (also known as Murray Island) to the North of Raine Island, in the Torres Strait. The reef with coral, waves breaking out to sea, clam shells, fish, seeing the seabirds, sharks, whales, and the turtles.

Raine Island is very important to me because of our history. Our ancestors were seafarers – traveling from Mer to Papua New Guinea, mainland Australia, Solomon Islands and Fiji. We would follow the edge of the Great Barrier Reef down south and this would take us to Raine Island. Our forefathers told us stories about Raine Island that had been passed down through generations– my own grandfather told me stories about Raine Island. They would journey down to Raine and use the island for trade with Aboriginal people. They would trade resources such as turtles, shells, canoes and drums, in exchange for red ochre and bird feathers to take back home.

Raine Island faces an uncertain future. I would like to see traditional knowledge and western science combining to find the answers for the Raine Island – cultural Traditional knowledge which has been passed down through generations and science must work together for the future of Raine Island and the green turtles.

Katharine Robertson

Senior Project Officer for the Raine Island Recovery Project, at the Department of Environment and Science, Australia.

My first trip to Raine Island was during the hatching season in 2015

Growing up, my family used to take me to a turtle nesting site on mainland Australia, where I first heard about the world’s most important turtle rookery - Raine Island, and later I did an honours research project on turtles as part of my science degree. I now work for the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, and my first trip to Raine Island was during the hatching season in 2015. The world’s most important turtle rookery, It was an amazing experience, but it was also heart-breaking because I saw the countless eggs that had died after tidal inundation flooded much of the nesting beach.

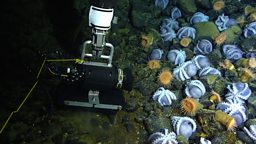

Scientists have been studying the green turtles at Raine Island since 1974. Fifty years of data has allowed us to understand what is happening on the island. But hatchling numbers weren’t being monitored initially, and it wasn’t until the mid-1990’s that it was identified how many eggs were dying before hatching, drowned by tidal inundation. Since then we have used industrial machinery, shipped all the way from mainland Australia, to reprofile the beach and raise it above the risk zone, doubling the amount of viable nesting habitat on the island. We have seen an increase in hatching success of eggs that can boost the population. We don’t see the mass numbers of dead eggs I saw in my first visit to the island.

It is incredible to be part of work that directly contributes to the conservation of green turtles and to be able to see first-hand the difference our actions have made.

However, I’m concerned for long term future of this green turtle population. Higher sand temperatures produce female hatchlings. In a warming world, today almost all the hatchlings from Raine Island are female. So long term we may not have enough males to sustain this population.

During filming for Planet Earth III, I came across a nesting turtle that was first tagged in 1984. Assuming that was her first nesting season, she would be around 66 years old. So it’s quite possible she hatched the year of Sir David’s visit. It’s nice to imagine she may even be the same turtle that David released in 1957. Despite the challenges of her lifetime, it’s heartening that she is still returning to lay her eggs. Let’s hope her kind will do so for generations to come.

Braydon Moloney

Cameraman for ‘Making Planet Earth III’

a once-in-a-lifetime experience

I first heard of Raine Island on an old TV documentary I saw once as a kid growing up in Australia. It had always been a dream to visit, but given the difficulties in getting there, and the need to be invited by the Wuthathi and Meriam Traditional Owners, I never thought I'd actually go there. You can imagine my excitement when the Planet Earth III team contacted me.

We arrived at Raine Island in the middle of the day. It was scorching hot, barren and hostile, with the glare of the sun reflecting harshly off the water and the white sand. And the only turtle in sight was dead, cooked in its own shell. Honestly, just for a moment, I couldn't help but wonder if we'd actually come to the right place.

But as the sun and the temperature dropped, the island transformed into a sublimely beautiful form. And then the nesting turtles started emerging from the water. First in their tens, then hundreds, and by the end of the night the scientists had counted 5000 nesting females.

The nights on Raine were beautiful. The turtles did their thing, as they have for countless millennia, while the milky way wheeled across the sky. It was supremely tranquil, even though the beach was literally heaving with life. I've never experienced anything like it.

Raine Island is a place you can only visit in the company of its Wuthathi and Meriam Traditional Owners, and I wouldn't have wanted it any other way. Our cultural advisors Keron and Falen shared the stories of their people, and helped us to understand the island from an indigenous perspective. It was remarkable to see that the commodities which Wuthathi and Meriam people have collected and traded there for thousands upon thousands of years - turtle shells, clams, tropicbird feathers - still exist in abundance, thanks to the care and protection Raine has been given.

Before this shoot, I was aware that climate change was skewing the gender balance of certain reptiles, turtles included, but I had no idea how dramatic the problem has become. I was floored when the Planet Earth III production team shared their research notes with me. 99% of green turtle hatchings on Raine are female, and it's been that way (or close to) for the last 20 years. This is the world's largest green turtle nursery we're talking about. If males aren't being born here, then there aren't many other places they can be. A population crash is imminent, and that terrifies me.

But it was during my time with the scientists and Traditional Owners on Raine that I learned something even worse. The island itself is under siege from rising sea levels. The rangers and Traditional Owners are working tirelessly to mitigate the impact as and where they can, but you can't hold back the sea forever. Without serious commitments to decarbonisation, the world's largest green turtle nursery will disappear beneath the waves, taking with it tens of thousands of years of unbroken indigenous connection.

To visit Raine Island was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. It saddens me deeply to know that the spectacle we captured could well disappear in the next few years. But I'm humbled to have played a small part in bringing the story of Raine's uncertain future to the world. Raine Island will forever remain a special place to me, and I hope that humanity can work to ensure it survives for generations to come.