5 scientists who changed the way we see nature

celebrates some of the most inspiring figures in the history of natural sciences.

1. Edward Tyson: The father of comparative anatomy

considered each animal to be a world of wonders. He believed that understanding how animals worked would enable us to understand human beings.

Born in 1651, Tyson was a highly skilled anatomist and among the first people in his field to compare the anatomy of animals with that of humans.

For his dissection of a chimpanzee he kept the bodies of humans and monkeys in mind. Tyson noted the chimp had more similarities with humans than with monkeys, essentially identifying a new group of animals - the apes.

Tyson was working before the systematic approach to classifying the natural world had been established and his work laid the foundations for scientists such as Carl Linnaeus to develop a useful way of ordering the natural world.

Why studying a chimpanzee was forward-thinking

Richard Sabin and Professor Erica Fudge explain the significance of Tyson's study.

2. Antoni van Leeuwenhoek: The father of microbiology

discovered a whole new world. The Dutch draper, born in 1632, was the first person to see bacteria, to see the cells that make up blood, to see microorganisms in water, and to understand the significance of sperm.

Over his long life he made hundreds of simple single lens microscopes, often designed and made for specific specimens and achieved magnifications that other microscopists at the time could not begin to approach.

Van Leeuwenhoek had unlimited curiosity and went to great lengths to attain specimens to observe, even cultivating them on his own body!

Leeuwenhoek opened up a miniature world captivating and disturbing the public in equal measure.

Under the microscope: The swimming world in our teeth

Keith Moore from the Royal Society describes van Leeuwenhoek's examination of tooth grit

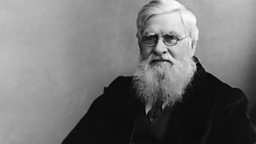

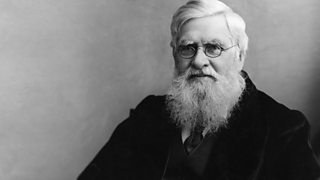

3. Alfred Russel Wallace: The father of evolutionary biogeography

The elegant Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection is one of the most important discoveries in the history of science. Two men, and Charles Darwin, are named as the co-discoverers but if it weren’t for Wallace the theory might never have been published.

Wallace was born in 1823 and as a young man had become fascinated by the idea that species might evolve. He was determined to discover the mechanism.

He travelled the world looking for clues and it was in 1858 while he was in Indonesia suffering from malaria that the concept of natural selection as the mechanism first came to Wallace.

Unknown to Wallace, Charles Darwin had come to the same conclusion many years earlier and when he received a short essay from Wallace detailing his idea, Darwin was spurred to action and the theory was jointly presented to the just weeks later.

It took time for the scientific establishment to accept this bold new idea but it completely changed the way we understand the natural world.

4. Franz Baron Nopcsa: The father of paleobiology

was a Hungarian aristocrat and one of the first people to think creatively about how extinct animals might have behaved.

Prior to Nopsca, palaeontologists were only interested in naming and describing dinosaurs and other extinct forms of life without considering how they might have lived their lives.

Among Nopsca’s ideas was that some dinosaurs might have cared for their young. This was dismissed at the time as fantasy but the many discoveries of fossilised dinosaurs watching over their nests have since supported his theory.

Not all of Nopsca’s ideas were so accurate but he still had the freedom of thought and confidence to explore new theories.

5. Sir Hans Sloane: The father of the British Museum

born in 1660, is probably the most prolific collector in history and he had eclectic tastes. Although the bulk of his collection was plant and animal specimens, he also collected coins and medals, books and manuscripts, statues, drawings and apparently had a particular love of shoes.

It was the contacts he acquired through his work as a physician and his generous treatment of the less wealthy in society that enabled Sloane to collect so prolifically. Ships captains, traders in local markets, explorers and aristocrats returning from their travels would bring him objects they had acquired.

But it is what Sloane did with his collection that makes him a true natural history hero.

When he died in 1753, his will stated that his entire collection of 71,000 objects should be offered to the government for the sum of £20,000 - well below its value.

Following a lottery to raise the cash and an act of parliament, the was born which later gave rise to the in 1881 and the in 1973.

Sloane’s generous gift to the nation began a new era of publically owned museums and was part of the transition between collecting for curiosity and using collections to better understand the world.